Buying Running Shoes on StockX:

Considering the pros and cons of the emergence of hypebeast culture in running.

“‘95 Air Max cause I’m a dope runner / I’m ballin’ like an athlete but got no jumper” - Gucci Mane

Alright, I’ll say it: it’s cool as sh*t to buy running shoes designed in an atelier in Paris. I don’t know what that means, but it’s friggin’ cool.

At the same time, it’s hard not to question whether the introduction of high-fashion (and its associated high-costs) into running footwear and apparel advances the sport and the surrounding culture or simply serves to (further) erode its accessibility.

Over the three decades that I have cared a bit too much about sneakers, in general, and running shoes, in particular, this little corner of the sneaker industry has always placed an emphasis on integrating thoughtful design, creativity, and technical innovation into the end product. From the launch of the double-cushioned split-tongue Gel-Lyte 3 in 1990 to last Fall’s arrival of adidas’s $500 entry into the ongoing arms-race in racing shoe technology, I’ve been around for and (overly) excited about advances in this field for most of my conscious life.

In essence, the underlying phenomenon is not new, per se, but the modern expression - i.e., limited (damn near impossible to cop) product runs, incredibly high (downright outrageous) prices, and increasingly impressive (obnoxiously over-the-top) marketing campaigns - begs the question: is this good? I’d like to, at the very least, start a discussion on this subject, because it sits at the center of a much greater challenge within running (and other niche sports): how do you elevate the social and cultural capital of a sport while ensuring that it remains accessible and inclusive?

To that end, let’s start by tackling some introductory questions:

What the hell am I am talking about?

What are the positives of this emerging trend?

What are the concerns/challenges?

Now what?

What the hell am I am talking about?

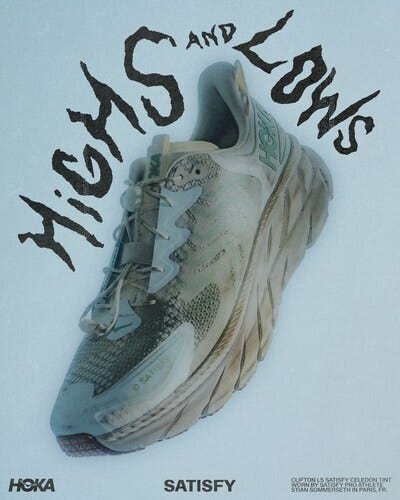

At the start of this year, Hypebeast posted an article on the emergence of brands that marry the technical sophistication of modern running gear with the stylistic sensibilities of high-fashion. Two brands mentioned in the article are Norda and Satisfy, both of which have established cult-like followings for their products.

Now, there’s much, much more to unpack with both of these brands and the broader ecosystem in which they operate, but my intention is to focus on something much more narrow.

Specifically, this:

And this:

Shoes like the Zegna Norda 001 and the HOKA Clifton LS Satisfy represent a new, and growing, segment of the running shoe market: the high-end, hypebeast-oriented collab. To qualify for this category, a sneaker must:

Be a jointly issued product: typically, this is a partnership between a running-centric brand and one that is fashion, design, or, more simply, hype-focused.

Have a limited product run: the goal is to suppress supply.

Possess a price point that: starts at “prix-fixe menu at Michelin Star restaurant” and escalates to “I could have flown to France instead of buying this sh*t.”

Need to be actually runnable: Even if a portion of the purchasing audience isn’t actually running in them, the product itself still needs to be able to actually serve that purpose (actually!).

The first and most famous example of this type of shoe arrived as part of the 2017 design collaboration between Virgil Abloh and Nike called, simply, The Ten. This partnership included - you’re not gonna believe this - ten interpretations of classic Nike sneaker silhouettes. One of the models included in this line was the Zoom Fly SP, which, as you can see at the link, can currently be purchased on StockX for as “low” as approximately $450 for a size 6.5 and up to nearly $7000 for a size 13. I have seen these being worn to run in San Francisco, so there is (very limited and very anecdotal) evidence that these sorts of shoes are not simply a streetwear statement piece, but rather, they serve that role and have a practical application, too.

In the eight years since the launch of The Ten, this type of sneaker has gradually grown from novelty to normal, with the past two years marking a massive uptick in the number and variety of these sorts of shoes.

(NOTE: I have created a list of all releases and will share links to available pairs on StockX in a future post)

And so, again, I come here as a fan, a friend, and someone trying to wrestle with whether this is a net good for the social, cultural, and technical advances in the sport and in the primary equipment required to run. To that end, let’s now look at why I think this is pretty darn cool.

What are the positives of this emerging trend?

There is not a ton of overlap between sneakerheads and long-distance runners, which is a damn shame. Core to both groups is a deep care and concern for what they put on their feet, an intimate understanding of midsoles and materials, and an appreciation for innovation and thoughtful design. Oh, and I cannot think of two groups more excited to spend a whole bunch of time just starin’ at shoes. Which is one reason it’s rad to see this sub-genre of sneaker start to takeoff. But it’s not the specific groups that makes this so damn awesome. Rather, it’s exciting because it builds rapport between parties that always shared a common bond, but never had much reason to connect or to celebrate it.

Beyond creating connections across communities, the hype-oriented running shoe is also worthy of praise because of the heightened attention it is bringing to the primary tool of the sport to an audience that extends well beyond runners. Yes, innovation in the technical specifications of running shoes remain the most important element of advances in shoes, but things like subtle distinctions in color, modifications of materials, and even the inclusion of multiple brand logos offers Easter Eggs and genuinely elevated product. This creates an aura of cool around the sport and does so via design, creativity, and technical innovation.

This is all very, very good. And yet, it’s still imperative to ask:

What are the concerns/challenges?

Earlier, the Zegna x Norda 001 was highlighted as a recent example of this wave. It is, to be sure, a wonderfully constructed shoe. It is also a shoe that costs as much as a used Kia.

Generally speaking, it’s helpful to avoid falling into good/bad binaries when constructing arguments about non-quantifiable matters. But this is bad. Norda’s standard offering already costs around $300, which is already slightly absurd, but doubling that? For some subtle design tweaks and the inclusion of a brand associated with well-tailored suits? Yeah, nah.

And before you say “but didn’t you just say that you love this stuff?”

Yes, I did. And, yes, I do.

But that love is not without caveats or conditions. And one such caveat is that the enthusiasm for these products is dramatically diminished when the price is comparable to a stay at the Four Seasons (not the one in the Seychelles, but, like, the Four Seasons in Toronto). It’s hard to say where, exactly, the tipping point for pricing is, but you know you’re there when you’re accurately comparing the cost of a sneaker to a stay at a five-star hotel.

What’s most unfortunate about the +$600 trail shoe is that it takes away from what I previously mentioned: the celebration of design and collaboration between what, until very recently, were unlikely creative bedfellows. If the discussion centers on the price, then we’ve lost the thread.

Similarly, even if the price isn’t exclusionary, the limited production runs certainly are. Let’s take another example: The Palace x Salomon XT-Wings 2

Look, this is a silhouette that is available in a variety of colors via general release on the Salomon site. Sure, fine. But you don’t want the general release pair. You want the cool pair. And the cool pair sold out faster than you could enter the webstore. Of course, this phenomenon is quite common across the sneaker and streetwear worlds, but that doesn’t make it a good thing. Moreover, it’s not altogether clear that slightly larger runs affect the ability to sell product or even to price them at a level that would otherwise be offputting.

Scarcity for scarity’s sake is just a private, exclusionary club.

Running is fun. Streetwear is fun. Not being able to find the sh*t you want: NOT FUN.

Now What?

It’s a net good for the sport to have running gear spotlighted by brands that are driving culture and fashion forward, because it suggests that running and, more specifically, running shoes can be vehicles for showcasing sports innovation and celebrating high-end design. At the same time, the price and limited product runs constraint just how much of a good thing they can ever be.

I still don’t know if this wave will ultimately prove to be a positive, but I do know that I am excited to explore this issue further. Sport was never exclusively about competition and now, perhaps more than ever, the social and cultural capital associated with shoes (and apparel) will play a significant role in shaping the future of running (and other niche sports).